Large-scale marine protected areas in 2016-2017 (Source: Big Ocean)

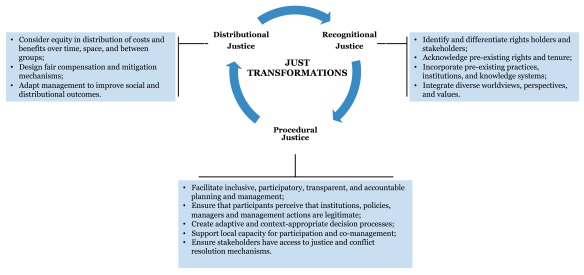

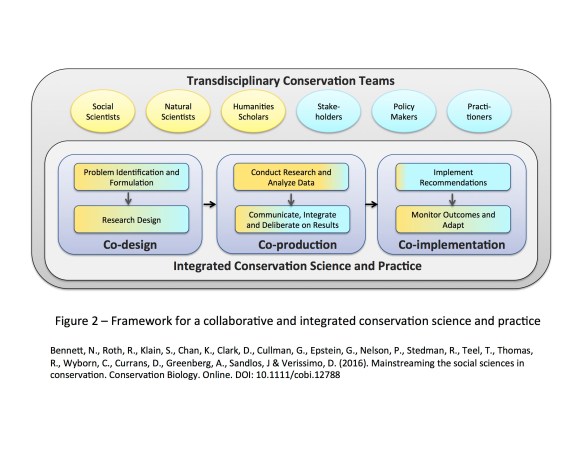

More than two years ago, I took up a Fulbright Visiting Scholar position in the School of Marine and Environmental Affairs at the University of Washington with Dr. Patrick Christie. Along with a team of collaborators from academic institutions and conservation organizations, we began the lengthy process of applying for funding and then co-organizing a global “Think Thank on the Human Dimensions of Large Scale Marine Protected Areas”. The meeting, which took place in February 2016 in Honolulu, Hawaii, was attended by more than 125 scholars, practitioners, traditional leaders, managers, funders and government representatives from around the world. Through facilitating a dialogue with all participants, we aimed to co-produce knowledge at a global scale about how human dimensions considerations might be incorporated into the planning and ongoing management of large scale marine protected areas. The think tank led to a “A Practical Framework for Addressing the Human Dimensions of Large-Scale Marine Protected Areas” and a subsequent academic article (link – see abstract below). This engagement and process demonstrates the benefits of global collaborations and how knowledge co-production processes can lead to the development of both practical and academic insights on global environmental challenges.

Participants of the Think Tank on the Human Dimensions of Large-Scale Marine Protected Areas

Christie, P. Bennett, N. J., Gray, N., Wilhelm, A., Lewis, N., Parks, J., Ban, N., Gruby, R., Gordon, L., Day, J., Taei, S. & Friedlander, A. (2017). Why people matter in ocean governance: Incorporating human dimensions into large-scale marine protected areas. Marine Policy, 84, 273-284. (link)

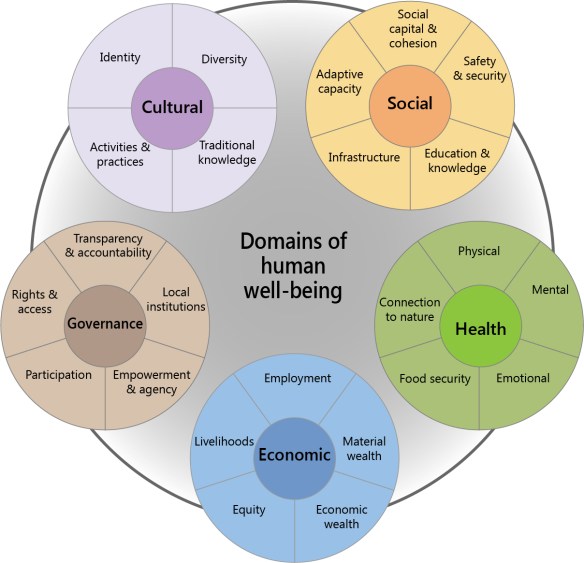

Abstract: Large-scale marine protected areas (LSMPAs) are rapidly increasing. Due to their sheer size, complex socio-political realities, and distinct local cultural perspectives and economic needs, implementing and managing LSMPAs successfully creates a number of human dimensions challenges. It is timely and important to explore the human dimensions of LSMPAs. This paper draws on the results of a global “Think Tank on the Human Dimensions of Large Scale Marine Protected Areas” involving 125 people from 17 countries, including representatives from government agencies, non-governmental organizations, academia, professionals, industry, cultural/indigenous leaders and LSMPA site managers. The overarching goal of this effort was to be proactive in understanding the issues and developing best management practices and a research agenda that address the human dimensions of LSMPAs. Identified best management practices for the human dimensions of LSMPAs included: integration of culture and traditions, effective public and stakeholder engagement, maintenance of livelihoods and wellbeing, promotion of economic sustainability, conflict management and resolution, transparency and matching institutions, legitimate and appropriate governance, and social justice and empowerment. A shared human dimensions research agenda was developed that included priority topics under the themes of scoping human dimensions, governance, politics, social and economic outcomes, and culture and tradition. The authors discuss future directions in researching and incorporating human dimensions into LSMPAs design and management, reflect on this global effort to co-produce knowledge and re-orient practice on the human dimensions of LSMPAs, and invite others to join a nascent community of practice on the human dimensions of large-scale marine conservation.

Abstract: The conservation community is increasingly focusing on the monitoring and

Abstract: The conservation community is increasingly focusing on the monitoring and