I was in Ottawa last week discussing marine protected areas in Canada. While there, I presented a policy brief titled “Making Real Progress on Marine Protected Areas in Canada” to the All Party Ocean Caucus. The brief can be found here and the text of the policy brief follows below.

Liber Ero Fellows and Members of the All-Party Ocean Caucus, October 24, 2016, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada (From left to right: MP Elizabeth May (Green), David Miller (WWF-Canada), MP Fin Donelly, Dr. Kim Davies (Dalhousie), MP Scott Simms, Dr. Nathan Bennett (UBC/UWash), Dr. Aerin Jacob (UVic), Dr. Sally Otto (UBC).

Making Real Progress on Marine Protected Areas in Canada

Creating effective and successful networks of marine protected areas in Canada requires attention to all elements of Aichi Target 11 and to international best practices for incorporating ecological, socio-economic, cultural and governance considerations.

Federal government ministerial mandate letters 2015, DFO: “Work with the Minister of Environment and Climate Change to increase the proportion of Canada’s marine and coastal areas that are protected – to five percent by 2017, and ten percent by 2020 – supported by new investments in community consultation and science.”

Convention on Biological Diversity, Aichi Target 11: “By 2020, at least 17 per cent of terrestrial and inland water areas and 10 per cent of coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services, are conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well-connected systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, and integrated into the wider landscape and seascape.”

Ecologically significant areas in the Great Bear Sea. Photo credit: Ian McAllister/Pacificwild (pacificwild.org) – Used with permission.

As a signatory to the Convention on Biological Diversity, Canada is striving to achieve the ambitious goal of 10% coverage of coastal and marine areas in networks of marine protected areas (MPAs) by 2020. Key points to ensure that MPA networks are effective and successful are summarized below:

- More than just area – Aichi Target 11 focuses on more than just the amount of area protected (i). Creating ecologically effective MPA networks also requires attention to: representation of all habitats, inclusion of unique and biologically significant areas, connectedness, and consideration of biodiversity and ecosystem service values (ii).

- Management effectiveness – Only 24% of protected areas are managed effectively globally (iii). Effective management requires adequate government funding, capacity and enforcement. Ongoing research programs are also needed to monitor and evaluate social and ecological outcomes and guide adaptive management (iv).

- Integrated ocean and coastal planning – The overall success and effectiveness of MPAs increases when integrated into a broader system of marine and coastal management that takes into account multiple stressors and promotes actions to mitigate the impacts of development (v).

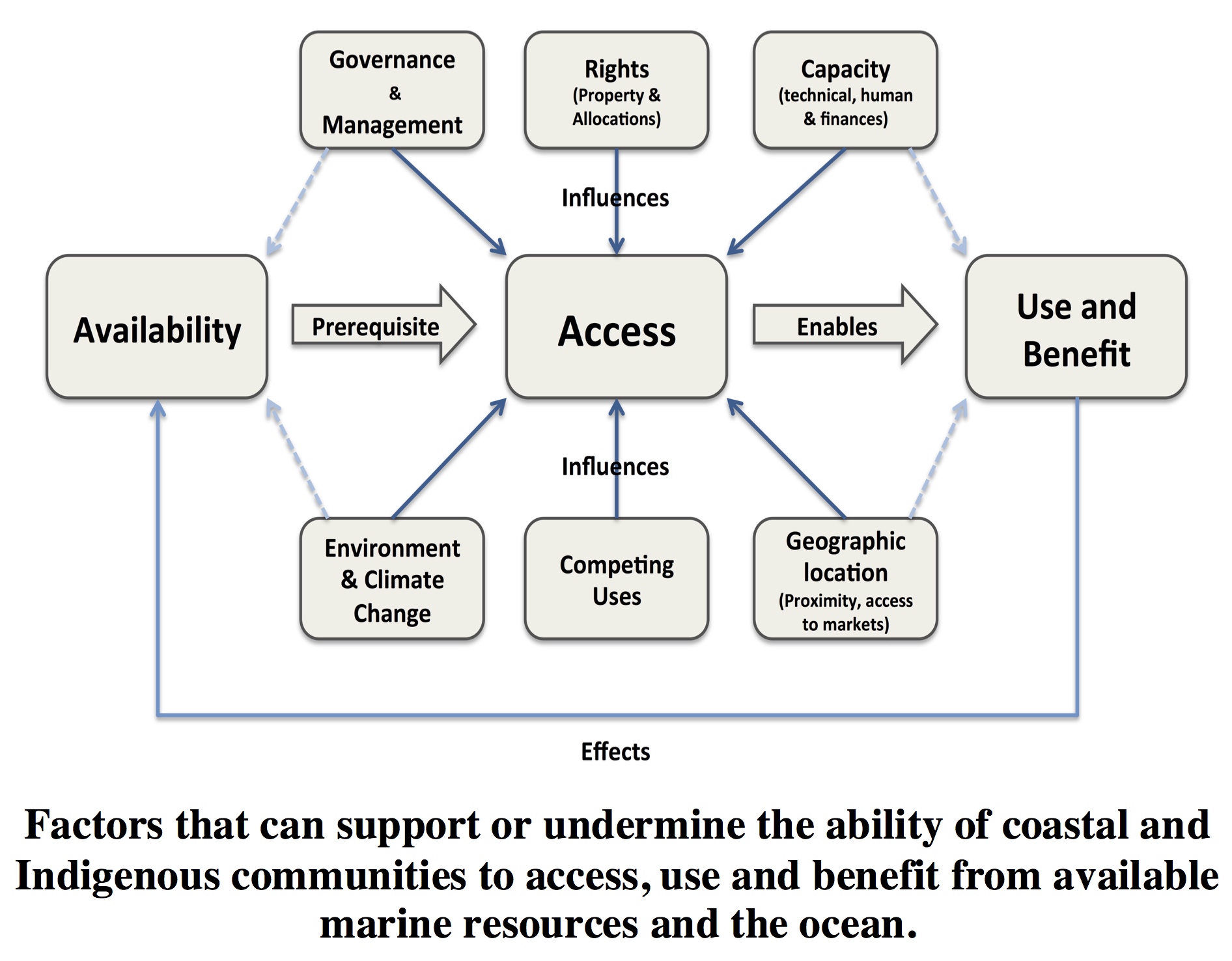

- Socio-economic and cultural considerations – Aichi Target 11 requires that MPAs are “equitably managed” which requires that social, economic and cultural considerations are factored into planning and management. In particular, there is a need to understand and balance the social and economic impacts of MPAs for different stakeholders during network planning and to incorporate cultural considerations and Aboriginal peoples’ rights into management plans (vi).

- Good governance – Good governance during planning, implementation and management is a key to the success of conservationvii. This means that decision-making processes and co-management structures need to be inclusive, participatory and transparent and respectful of the preferential rights of Aboriginal peoples and right relationships with First Nations’ governments (vii).

- “Other effective area-based conservation measures” (OEACBM) – What counts as an OEABCM needs to be clearly defined in the spirit of the Aichi target and in alignment with all the elements listed above (viii). This means that managed areas that benefit only one species or habitat should not be considered equivalent to a marine protected area. Consideration should also be given to other governance models that effectively conserve biodiversity, including Indigenous and Community Conserved Areas and Tribal Parks (ix).

Currently, MPAs cover 1.1% of Canada’s oceans (x)

Getting from 1.1% (497,600km2) to the milestone of 10% is a significant challenge that will require collaboration between multiple levels of government and different jurisdictions. For example, MPAs fall under the authority of Fisheries and Oceans, Parks and Environment & Climate Change Canada. To facilitate the achievement of the targets the government is advised to build on past and ongoing marine planning process of provincial, territorial and Aboriginal governments, such as the Marine Plan Partnership, First Nations Marine Planning, the PNCIMA process and the Northern Shelf Bioregion MPA planning process (xi).

Resolutions:

Fishing boat on the Pacific Coast of Canada. Photo credit: Natalie Ban. Used with permission.

- Ensure that all elements of Aichi Target 11 are taken into account when planning MPA networks in Canada.

- Incorporate lessons from global experiences of creating MPAs related to effective management, good governance and integrated planning

- Account for social, economic and cultural considerations in planning and management of MPAs.

- Develop adequate co-management structures and decision-making processes that include First Nations as equal partners.

- Support multi-jurisdictional collaboration and build on previous initiatives.

- Ensure that MPA planning and management is guided by both natural and social science. Implement monitoring and evaluation to guide adaptive management.

Prepared by Dr. Nathan Bennett (University of British Columbia) and Dr. Natalie Ban (University of Victoria) with input from members of the OceanCanada Partnership (oceancanada.org). Please contact us should you wish further information: nathan.bennett@ubc.ca and nban@uvic.ca

(i) Spalding, M. et al. Building towards the marine conservation end-game: consolidating the role of MPAs in a future ocean. Aquatic Cons 26, 185–199 (2016).

(ii) Jessen, S. et al. Science Based Guidelines for Marine Protected Areas and Marine Protected Area Networks in Canada. 58 (Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, 2011).

(iii) Leverington, F. & et al. Management effectiveness evaluation in protected areas – a global study (2nd ed). (U of Queensland, 2010).

(iv) Pomeroy, R. S., Parks, J. E. & Watson, L. M. How is your MPA doing?: A guidebook of natural and social indicators for evaluating marine protected area management effectiveness. (IUCN, 2004).

(v) Nowlan, L. Brave New Wave: Marine Spatial Planning & Ocean Regulation on Canada’s Pacific. J. of Env Law Prac 29, 151–198 (2016).

(vi) Rodríguez-Rodríguez, D., Rees, S. E., Rodwell, L. D. & Attrill, M. J. IMPASEA: A methodological framework to monitor and assess the socioeconomic effects of marine protected areas. Env Sci Pol 54, 44–51 (2015); Ban, N. C. et al. A social–ecological approach to conservation planning: embedding social considerations. Front Ecol Env 11, 194–202 (2013).

(vii) Bennett, N. J. & Dearden, P. From measuring outcomes to providing inputs: Governance, management, and local development for more effective marine protected areas. Mar Poli 50, 96–110 (2014).; Burt, J.M., et al. 2015. Marine Protected Area Network Design Features that Support Resilient Human-Ocean Systems. Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, Canada.

(viii) Mackinnon, D. et al. 2015. Canada and Aichi Biodiversity Target 11: understanding ‘other effective area-based conservation measures’ in the context of the broader target. Biodiversity and Conservation 24:3559-3581; DFO. Guidance on identifying ‘other effective area-based conservation measures’ in Canadian coastal and marine waters. (DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat, 2016).

(xi) See: http://www.facebook.com/tlaoquiaht/about/; http://www.iccaconsortium.org; Wilson, P., McDermott, L., Johnston, N. & Hamilton, M. An Analysis of Intenational Law, National Legislation, Judgements, and Institutions as they Interrelate with Territories and Areas Conserved by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities – Report No 8. Canada. (Natural Justice, 2012).

(x) Data: http://www.ccea.org; Visualization: www.wwf.ca/conservation/oceans/

(xi) mappocean.org; mpanetwork.ca/bcnorthernshelf/other-initiatives/; mpanetwork.ca

A group representing academics, Indigenous peoples, fishers, and NGOs recently published a

A group representing academics, Indigenous peoples, fishers, and NGOs recently published a

Abstract: The conservation community is increasingly focusing on the monitoring and

Abstract: The conservation community is increasingly focusing on the monitoring and

governance, and (2) be implemented using actions that undermine human security and livelihoods, or (3) produce impacts that reduce social–ecological well-being. Future research on ocean grabbing will: document case studies, drivers and consequences; conduct spatial and historical analyses; and investigate solutions. The intent is to stimulate rigorous discussion and promote systematic inquiry into the phenomenon of ocean grabbing.

governance, and (2) be implemented using actions that undermine human security and livelihoods, or (3) produce impacts that reduce social–ecological well-being. Future research on ocean grabbing will: document case studies, drivers and consequences; conduct spatial and historical analyses; and investigate solutions. The intent is to stimulate rigorous discussion and promote systematic inquiry into the phenomenon of ocean grabbing.