Tag Archives: environmental governance

New Paper: Just Transformations to Sustainability

A group of co-authors and I have published a new open access paper titled Just Transformations to Sustainability (Link to PDF). In this paper, we argue that sustainability transformations cannot be considered a success unless social justice is a central concern. Here, we define just transformations as “radical shifts in social–ecological system configurations through forced, emergent or deliberate processes that produce balanced and beneficial outcomes for both social justice and environmental sustainability.” We also provide a framework that highlights how recognitional, procedural and distributional justice can be taken into account to navigate just transformations in environmental sustainability policies and practice.

A practical framework for environmental governance

A practical framework for environmental governance (Bennett & Satterfield, 2018)

Managing the social impacts of conservation

Concerns about the negative consequences of conservation for local people have prompted attention toward how to address the social impacts of different conservation projects, programs, and policies. Inevitably, when actions are taken to protect or manage the environment this will produce a suite of both positive and negative social impacts for local communities and resource users. Thus, a challenge for conservation and environmental decision-makers and managers is maximizing social benefits while minimizing negative burdens across social, economic, cultural, health, and governance spheres of human well-being. The last decade has seen significant advances in both the methods and the metrics for understanding how conservation and environmental management impact human well-being. There has also been increased uptake in socio-economic monitoring programs in conservation organizations and environmental agencies. Yet, little guidance exists on how to integrate the results of social impact monitoring back into conservation management and decision-making. We recommend that conservation organizations and environmental agencies take steps to better understand and address the social impacts of conservation and environmental management. This can be achieved by integrating key components of the adaptive social impact management (ASIM) cycle outlined below, and in a new paper published today in Conservation Biology, into decision-making and management processes**.

Conservation and environmental management can have positive or negative impacts on the well-being of local communities.

|

Take away messages: Conservation and environmental management can produce both positive and negative social impacts for local communities and resource users. Thus it is necessary to understand and adaptively manage the social impacts of conservation over time. This will improve social outcomes, engender local support and increase the overall effectiveness of conservation. |

Adaptive social impact management

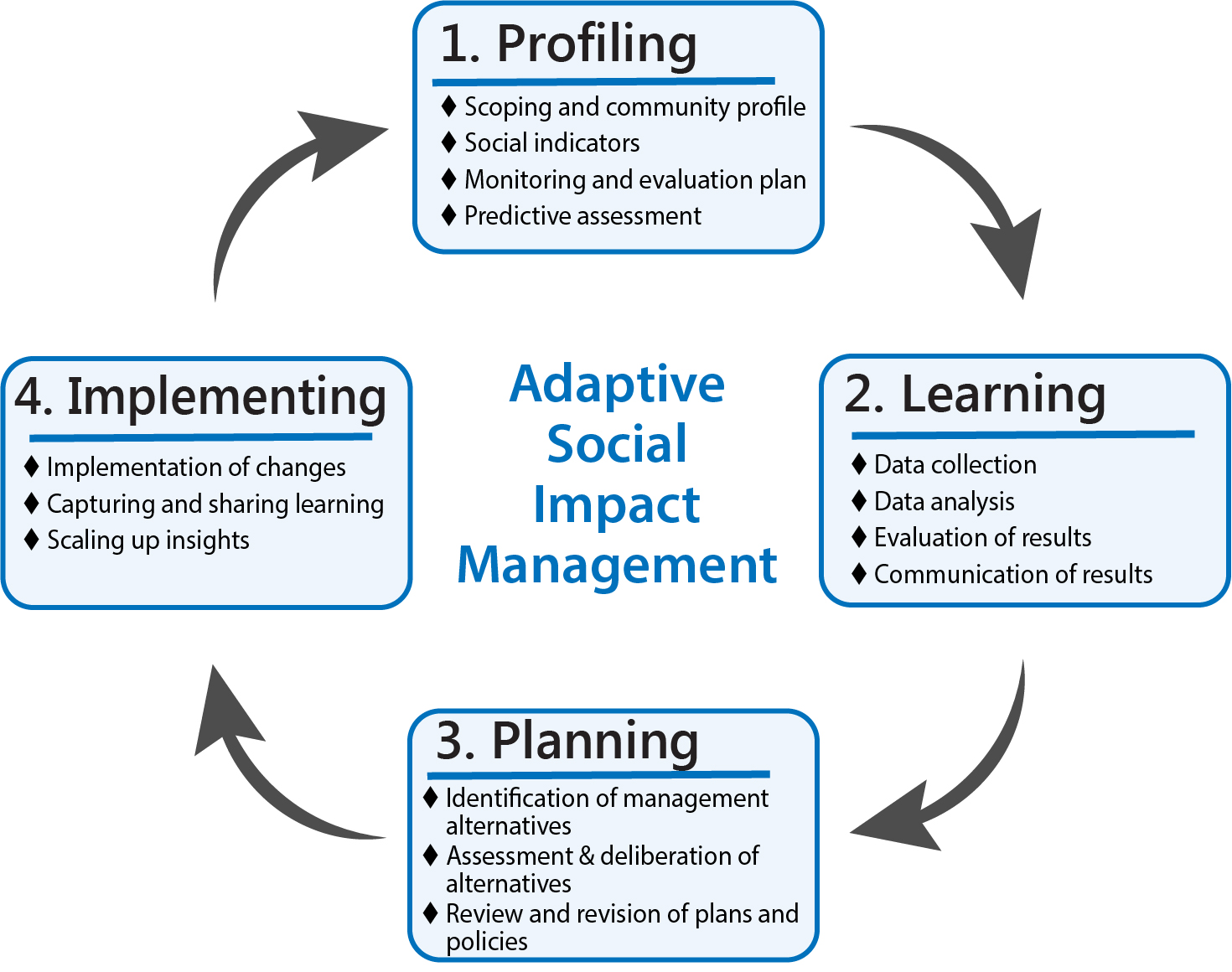

Adaptive social impact management (ASIM) is “the ongoing and cyclical process of monitoring and adaptively managing the social impacts of an initiative through the following four stages: profiling, learning, planning and implementing.”

The cycle of adaptive social impact management for conservation and environmental management.

- Profiling – The cycle begins with defining the scope and social profile for the social impact management program. This involves identifying spatial boundaries, timelines, and available resources, as well as creating a basic profile of the social system under consideration.

- Learning – The second stage focuses on developing an understanding of the actual positive and negative social impacts of the project to date as well as how and why these impacts have occurred. It involves data collection, analysis, evaluation, and communication.

- Planning – During the third stage, managers and practitioners identify alternative courses of action and their respective potential impacts, deliberate and make decisions regarding which actions to take, and revise management policies and plans accordingly.

- Implementing – The final stage is where decisions are put into action to adapt conservation and management. Lessons learned are shared across sites and to managers and policy-makers to inform decisions, policies and programs.

For more information, please refer to:

- POLICY BRIEF: Managing the social impacts of conservation, October 2017

- PUBLICATION: Maery Kaplan-Hallam & Nathan J. Bennett (2017). Adaptive social impact management for conservation and environmental management. Conservation Biology. Link: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cobi.12985/full

Contacts: Please email Maery Kaplan-Hallam (maerykaplan@gmail.com) or Dr. Nathan Bennett (nathan.bennett@ubc.ca).

Why people matter in ocean governance: Incorporating human dimensions into large-scale marine protected areas.

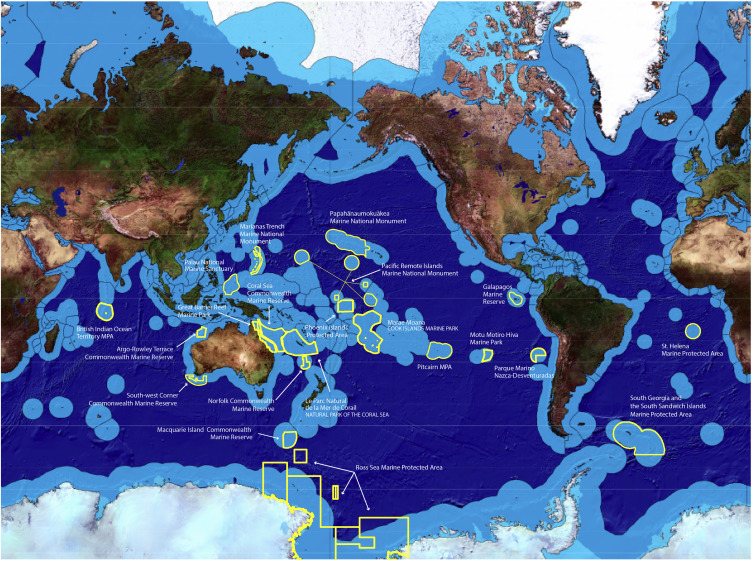

Large-scale marine protected areas in 2016-2017 (Source: Big Ocean)

More than two years ago, I took up a Fulbright Visiting Scholar position in the School of Marine and Environmental Affairs at the University of Washington with Dr. Patrick Christie. Along with a team of collaborators from academic institutions and conservation organizations, we began the lengthy process of applying for funding and then co-organizing a global “Think Thank on the Human Dimensions of Large Scale Marine Protected Areas”. The meeting, which took place in February 2016 in Honolulu, Hawaii, was attended by more than 125 scholars, practitioners, traditional leaders, managers, funders and government representatives from around the world. Through facilitating a dialogue with all participants, we aimed to co-produce knowledge at a global scale about how human dimensions considerations might be incorporated into the planning and ongoing management of large scale marine protected areas. The think tank led to a “A Practical Framework for Addressing the Human Dimensions of Large-Scale Marine Protected Areas” and a subsequent academic article (link – see abstract below). This engagement and process demonstrates the benefits of global collaborations and how knowledge co-production processes can lead to the development of both practical and academic insights on global environmental challenges.

Participants of the Think Tank on the Human Dimensions of Large-Scale Marine Protected Areas

Christie, P. Bennett, N. J., Gray, N., Wilhelm, A., Lewis, N., Parks, J., Ban, N., Gruby, R., Gordon, L., Day, J., Taei, S. & Friedlander, A. (2017). Why people matter in ocean governance: Incorporating human dimensions into large-scale marine protected areas. Marine Policy, 84, 273-284. (link)

Abstract: Large-scale marine protected areas (LSMPAs) are rapidly increasing. Due to their sheer size, complex socio-political realities, and distinct local cultural perspectives and economic needs, implementing and managing LSMPAs successfully creates a number of human dimensions challenges. It is timely and important to explore the human dimensions of LSMPAs. This paper draws on the results of a global “Think Tank on the Human Dimensions of Large Scale Marine Protected Areas” involving 125 people from 17 countries, including representatives from government agencies, non-governmental organizations, academia, professionals, industry, cultural/indigenous leaders and LSMPA site managers. The overarching goal of this effort was to be proactive in understanding the issues and developing best management practices and a research agenda that address the human dimensions of LSMPAs. Identified best management practices for the human dimensions of LSMPAs included: integration of culture and traditions, effective public and stakeholder engagement, maintenance of livelihoods and wellbeing, promotion of economic sustainability, conflict management and resolution, transparency and matching institutions, legitimate and appropriate governance, and social justice and empowerment. A shared human dimensions research agenda was developed that included priority topics under the themes of scoping human dimensions, governance, politics, social and economic outcomes, and culture and tradition. The authors discuss future directions in researching and incorporating human dimensions into LSMPAs design and management, reflect on this global effort to co-produce knowledge and re-orient practice on the human dimensions of LSMPAs, and invite others to join a nascent community of practice on the human dimensions of large-scale marine conservation.

How the popularity of sea cucumbers is threatening coastal communities

Coastal communities are struggling with the complex social and ecological impacts of a growing global hunger for a seafood delicacy, according to a new study from the University of British Columbia.

“Soaring demand has spurred sea cucumber booms across the globe,” says lead author Mary Kaplan-Hallam, who conducted the research as a master’s student with the Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability (IRES) at UBC.

“For many coastal communities, sea cucumber isn’t something that was harvested in the past. Fisheries emerged rapidly. Money, buyers and fishers from outside the community flooded in. This has also increased pressure on other already overfished resources.”

Sea cucumber can sell for hundreds–sometimes thousands–of dollars a pound. The “gold rush” style impacts of high-value fisheries exacerbate longer-term trends in already vulnerable communities, such as declines in traditional fish stocks, population increases, climate change and illegal fishing.

“These boom-and-bust cycles occur across a range of resource industries,” says co-author Nathan Bennett, a postdoctoral fellow at UBC. “What makes these fisheries so tricky is that they appear rapidly and often deplete local resources just as rapidly, leaving communities with little time to recover.”

Sea cucumber fishing season 2016 (Dzilam de Bravo, Yucatan, Mexico). Credit: Eva Coronado, National Polytechnic Institute, Mexico.

The researchers based their findings on a case study of Río Lagartos, a fishing community on Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula. For the past 50 years, small-scale commercial fishing has been the dominant livelihood of the community.

The town’s first commercial sea cucumber permits were issued in 2013, a significant economic opportunity for fishers in the region. The leathery marine animals are a delicacy in many parts of Asia, and as stocks have depleted there, demand has rapidly depleted fisheries across the globe.

A host of new challenges emerged in Río Lagartos as the sea cucumbers attracted outside fishers, money and patrons, according to the researchers’ interviews with community members.

“Resource management, incomes, fisher health and safety, levels of social conflict and social cohesion in the community are all impacted,” says Kaplan-Hallam. “The potential financial rewards are also causing local fishers to take bigger risks as sea cucumber stocks are depleted and diving must occur further from shore, with dire health consequences.”

Unfortunately, say the authors, this isn’t an isolated situation.

“There are many examples around the world where elite global seafood markets–abalone, sea urchins, sharks–are undermining local sustainability,” says Bennett. “If we want to sustainably manage fisheries with coastal communities, we need a better understanding of how global seafood markets impact communities and how to manage these impacts quickly. Think of it like an epidemic: it requires a rapid response before it gets out of control.”

###

The study “Catching sea cucumber fever in coastal communities” is published in Global Environmental Change

The research was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, MITACS, the Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship program, and the Liber Ero Fellowship program.

New article: An appeal for a code of conduct for marine conservation

A group of colleagues and I have just published an open access paper titled “An appeal for a code of conduct for marine conservation” in Marine Policy. In this paper, we propose that:

- Poor governance and social issues can jeopardize the legitimacy of, support for and long-term effectiveness of marine conservation.

- A comprehensive set of social standards is needed to provide a solid platform for conservation actions.

- This paper reviews key principles and identifies next steps in developing a code of conduct for marine conservation.

- The objectives of a code of conduct are to promote fair, just and accountable marine conservation.

- A code of conduct will enable marine conservation to be both socially acceptable and ecologically effective.

Abstract: Marine conservation actions are promoted to conserve natural values and support human wellbeing. Yet the quality of governance processes and the social consequences of some marine conservation initiatives have been the subject of critique and even human rights complaints. These types of governance and social issues may jeopardize the legitimacy of, support for and long-term effectiveness of marine conservation. Thus, we argue that a clearly articulated and comprehensive set of social standards – a code of conduct – is needed to guide marine conservation. In this paper, we draw on the results of an expert meeting and scoping review to present key principles that might be taken into account in a code of conduct, to propose a draft set of foundational elements for inclusion in a code of conduct, to discuss the benefits and challenges of such a document, and to propose next steps to develop and facilitate the uptake of a broadly applicable code of conduct within the marine conservation community. The objectives of developing such a code of conduct are to promote fair conservation governance and decision-making, socially just conservation actions and outcomes, and accountable conservation practitioners and organizations. The uptake and implementation of a code of conduct would enable marine conservation to be both socially acceptable and ecologically effective, thereby contributing to a truly sustainable ocean.

Press releases and coverage

- Code of conduct needed for ocean conservation, study says – Eureka Alert

- Does marine conservation need a “Hippocratic Oath”? – CBC

- Marine conservation must consider human rights – Nereus Program

Policy Brief: An appeal for a code of conduct for marine conservation (PDF LINK)

Reference: Bennett, N.J., Teh, L., Ota, Y., Christie, P., Ayers, A., Day, J.C., Franks, P., Gill, D., Gruby, R.L., Kittinger, J.N., Koehn, J.Z., Lewis, N., Parks, J., Vierros, M., Whitty, T.S., Wilhelm, A., Wright, K., Aburto, J.A., Finkbeiner, E.M., Gaymer, C.F., Govan, H., Gray, N., Jarvis, R.M., Kaplan-Hallam, M. & Satterfield, T. (2017). An appeal for a code of conduct for marine conservation. Marine Policy, 81, 411–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2017.03.035 [OPEN ACCESS]

Mainstreaming the social sciences in conservation

I just published a co-authored Open Access article in the journal Conservation Biology titled “Mainstreaming the social sciences in conservation“. In this article, we define conservation social science, examine the barriers to uptake of the social sciences in conservation, and suggest practical steps that might be taken to overcome these barriers.

Bennett, N., Roth, R., Klain, S., Chan, K., Clark, D., Cullman, G., Epstein, G., Nelson, P., Stedman, R., Teel, T., Thomas, R., Wyborn, C., Currans, D., Greenberg, A., Sandlos, J & Verissimo, D. (2016). Mainstreaming the social sciences in conservation. Conservation Biology. Online, Open Access. DOI: 10.1111/cobi.12788

Abstract

Despite broad recognition of the value of social sciences and increasingly vocal calls for better engagement with the human element of conservation, the conservation social sciences remain misunderstood and underutilized in practice. The conservation social sciences can provide unique and important contributions to society’s understanding of the relationships between humans and nature and to improving conservation practice and outcomes. There are 4 barriers – ideological, institutional, knowledge, and capacity – to meaningful integration of the social sciences into conservation. We provide practical guidance on overcoming these barriers to mainstream the social sciences in conservation science, practice, and policy. Broadly, we recommend fostering knowledge on the scope and contributions of the social sciences to conservation, including social scientists from the inception of interdisciplinary research projects, incorporating social science research and insights during all stages of conservation planning and implementation, building social science capacity at all scales in conservation organizations and agencies, and promoting engagement with the social sciences in and through global conservation policy-influencing organizations. Conservation social scientists, too, need to be willing to engage with natural science knowledge and to communicate insights and recommendations clearly. We urge the conservation community to move beyond superficial engagement with the conservation social sciences. A more inclusive and integrative conservation science – one that includes the natural and social sciences – will enable more ecologically effective and socially just conservation. Better collaboration among social scientists, natural scientists, practitioners, and policy makers will facilitate a renewed and more robust conservation. Mainstreaming the conservation social sciences will facilitate the uptake of the full range of insights and contributions from these fields into conservation policy and practice.

Download from here

Perceptions are Evidence and Key to Conservation Success

My latest publication, in the journal Conservation Biology, is titled “Using perceptions as evidence to improve conservation and environmental management”. In this article, I argue for a broader view of evidence in adaptive environmental management and evidence-based conservation. I clarify how perceptions can be used as a form of evidence to guide conservation decision making and action taking. Perceptions provide critical insights into how people view social impacts, ecological outcomes, governance processes and management. Peoples understandings and evaluations of these four factors ultimately determines their level of support for conservation. Conservation success depends on long-term local support.

Link to the article: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cobi.12681/abstract

Reference: Bennett, N. J. (2016). Using perceptions as evidence to improve conservation and environmental management. Conservation Biology. online.

Abstract: The conservation community is increasingly focusing on the monitoring and

Abstract: The conservation community is increasingly focusing on the monitoring and

evaluation of management, governance, ecological, and social considerations as part of a broader move toward adaptive management and evidence-based conservation. Evidence is any information that can be used to come to a conclusion and support a judgment or, in this case, to make decisions that will improve conservation policies, actions, and outcomes. Perceptions are one type of information that is often dismissed as anecdotal by those arguing for evidence-based conservation. In this paper, I clarify the contributions of research on perceptions of conservation to improving adaptive and evidence-based conservation. Studies of the perceptions of local people can provide important insights into observations, understandings and interpretations of the social impacts and ecological outcomes of conservation; the legitimacy of conservation governance; and the social acceptability of environmental management. Perceptions of these factors contribute to positive or negative local evaluations of conservation initiatives. It is positive perceptions, not just objective scientific evidence of effectiveness, that ultimately ensure the support of local constituents thus enabling the long-term success of conservation. Research on perceptions can inform courses of action to improve conservation and governance at scales ranging from individual initiatives to national and international policies. Better incorporation of evidence from across the social and natural sciences and integration of a plurality of methods into monitoring and evaluation will provide a more complete picture on which to base conservation decisions and environmental management.

Keywords: monitoring and evaluation; evidence-based conservation; conservation social science; environmental social science; protected areas; environmental governance; adaptive management

What is environmental governance?

Environmental governance is a topic that has received a fair amount of attention in the academic and applied literatures on conservation and environmental management in the last few years. However, there remains a significant amount of confusion about what governance is, how governance is different than management, and what topics and questions governance scholars examine. In this open access extended review in the journal Conservation Biology, I provide answers to these questions while reviewing Peter Jones’ book “Governing Marine Protected Areas: Resilience through Diversity“. Excerpts from the text of “Governing marine protected areas in an interconnected and changing world” follow below.

What is governance? – “Governance is an umbrella term that refers to the structures, institutions (i.e., laws, policies, rules, and norms), and processes that determine who makes decisions, how decisions are made, and how and what actions are taken and by whom.”

How does governance differ from management? – “Although the umbrella of governance facilitates (or undermines) effective environmental management, it can be differentiated from management as the resources, plans, and actions that result from the functioning of governance (Lockwood 2010). The objectives of both environmental governance and management are to steer, or change, individual behaviors or collective actions and, ultimately, to improve environmental and societal outcomes. Without good governance combined with effective management, [environmental management and conservation initiatives] are unlikely to succeed socially or ecologically (Bennett & Dearden 2014).”

What topics do environmental governance scholars examine? – “Scholarship on environmental governance has grown significantly over the last few decades, ranging in ecological scale from individual species (e.g., whales) to resources or ecosystems (e.g., forests, coral reefs) to global concerns (e.g., climate, oceans). Specific policy realms (e.g., fisheries, agriculture, or MPAs) are also the subject of governance analyses and planning. Environmental governance studies focus on 2 central and interrelated areas: governance design and implementation and governance performance…Environmental governance can be evaluated either or simultaneously on whether processes are fair and legitimate and whether outcomes are socially equitable or ecologically sustainable…Disagreement remains about whether outputs of governance analyses should be descriptive or prescriptive.”

What questions do environmental governance scholars explore? – “Questions and ideas that have been taken up by environmental governance scholars…[include]: How are individual and collective behaviors shaped by different governance institutions? What is the ideal governance structure for managing people and resources: community based, top down, or comanagement? How and why do governance institutions change and to what effect? What decision-making processes are more socially acceptable and lead to better ecological outcomes? What are the roles of different actors and organizations (e.g., governments, NGOs, private sector, local stakeholders, and resource users) in shaping governance processes and determining outcomes? How can governance address interconnected social-ecological systems and interactions across ecological, social, and institutional scales? How can governance be designed to fit different sociopolitical and ecological contexts? What limits are placed on governance by different social, political, and ecological factors? What norms or ideals (e.g., transparency, accountability, trust) should guide governance? What is the appropriate scale for governance to occur? How can collaboration and cooperation be facilitated most effectively? How can governance be designed to be stable and also to adapt to mounting social and ecological changes and unpredictable circumstances? These are not merely academic concerns. Insights provided by answers to these questions would help in the formulation of appropriate, acceptable, and supportive environmental governance policies and processes, enabling more effective management and ultimately enhancing…social and ecological outcomes.”

The full text of the article can be downloaded from the blue links below: