Tag Archives: marine conservation

Recommendations for mainstreaming equity and justice in ocean organizations, policies and practice

Addressing equity and justice issues has become a central concern of ocean policy and sustainability efforts. Yet, many ocean-focused governmental, non-governmental and funding organizations often lack the foundational knowledge, mandate, capacity, and diversity to be able to adequately account for and address equity and justice issues.

In a new opinion editorial, I provide six recommendations for how marine conservation and development organizations can establish a strong internal foundation for mainstreaming equity and justice issues in external marine policies, practices, programs and portfolios. These recommendations include the following:

- Develop awareness of past equity and justice issues in marine policy spheres where the organization works.

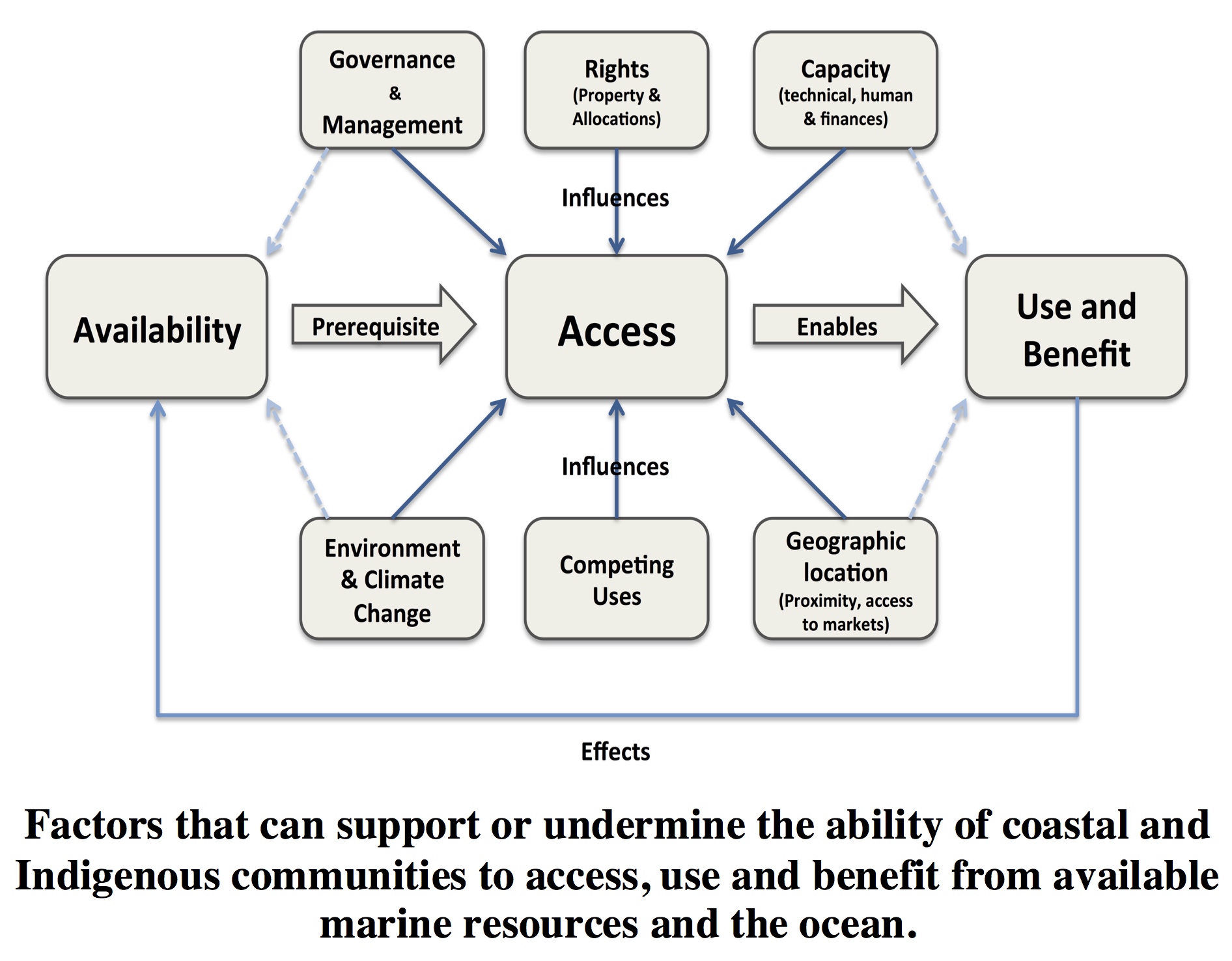

- Explore how equity and justice are defined and can be operationalized in marine policy and practice (see Figure 1).

- Mainstream equity and justice in organizational policies, practices, programs, and portfolios.

- Increase organizational human dimensions capacity and ability to think socially.

- Support marine social science research and engage with evidence regarding the human dimensions.

- Commit to internal organizational equity, diversity and inclusion as a foundation for external equity and justice work.

Creating strong organizational foundations is an important starting place and enabler for advancing equity and justice in the ocean. Read the editorial here.

Reference: Bennett, N.J. (2022). Mainstreaming Equity and Justice in the Ocean. Frontiers in Marine Science, 9. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2022.873572/full

Webinar Recording – Equity and Justice in the Ocean

If you missed my recent talk on “Equity and Justice in the Ocean” hosted by the Marine Social Science Network, you can watch a recording here.

The oceans are experiencing a rapid acceleration of both conservation and development activities. When poorly implemented or left unchecked, these activities can lead to environmental and social injustices for the coastal communities and populations who inhabit and rely on the ocean for livelihoods, food security, and cultural survival. In this talk, I examine the types of social injustices that are occurring in the ocean, discuss how social equity can be taken into account in efforts to promote ocean sustainability, and explore priority areas for future marine social science research on equity and justice in the oceans. My aim is to encourage greater engagement with equity and justice considerations in all ocean-focused organizations and in all decision-making processes related to ocean governance and management.

This talk will draw from and build on a number of recent papers related to these topics:

• Bennett, N. J. (2018). Navigating a just and inclusive path towards sustainable oceans. Marine Policy, 97, 139–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2018.06.001

• Bennett, N. J et al. (2019). Just Transformations to Sustainability. Sustainability, 11(14), 3881. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11143881

• Bennett, N. J. et al. (2019). Towards a sustainable and equitable blue economy. Nature Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0404-1

• Bennett, N. J. et al. (2021). Advancing Social Equity in and Through Marine Conservation. Frontiers in Marine Science. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.711538

•Bennett, N. J. et al. (2021). Blue growth and blue justice: Ten risks and solutions for the ocean economy. Marine Policy, 125, 104387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104387

Policy Brief: Marine Social Science and Ocean Sustainability

Around the world, the marine and coastal environment is occupied, used and relied on by coastal communities, small-scale fishers, and Indigenous peoples.

Background: Marine protected areas, marine spatial planning, fisheries management, climate adaptation and economic development activities are increasing across the world’s oceans. Coastal communities, indigenous peoples, and small-scale fishers also occupy, use and rely on the ocean and coastal environment for livelihoods, for sustenance, and for wellbeing. An understanding of the human dimensions of the peopled seas is required to make informed marine policy and management decisions. A diverse set of social science disciplines, methods, and theories can be applied to rigorously study the human dimensions of ocean and coastal issues and challenges. Insights from the marine social sciences include:

- Documenting the social context (eg, uses, benefits, values, rights, knowledge, culture) to inform planning and management;

- Characterizing and evaluating the appropriateness and effectiveness of governance processes and management actions;

- Assessing the impacts of conservation, management or development activities on coastal economics and human well-being; and,

- Identifying the social and institutional factors that influence people’s behaviours, actions or responses to identify effective interventions.

The marine social sciences must be part of the mandate and investments of national and international ocean science, policy and sustainability initiatives. Yet, marine social science often receives limited attention and investments from ocean-focused government agencies, NGOs and funders.

Recommendations: Recommended actions include:

- Policy-makers, managers and practitioners need to account for the human dimensions in all marine conservation, marine planning, fisheries management and ocean development decisions.

- Governments should ensure that ocean-focused laws, policies and planning processes require the consideration of social, cultural, economic and governance considerations.

- National and international ocean science and sustainability initiatives, such as the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021-2030), must include social science in their mandates and investments.

- Financial support is needed from ocean-focused government agencies, multi-lateral organizations, NGOs and funders for capacity, programs and infrastructure to enable applied and policy-relevant marine social science research.

|

KEY MESSAGES The pursuit of sustainable oceans must be informed by insights from the marine social sciences. Recent years have seen significant growth in conservation, management and development activities in the ocean. Coastal communities, indigenous peoples, and small-scale fishers also occupy and rely on the ocean for livelihoods, for subsistence, and for wellbeing. Thus, an understanding of the human dimensions is required to make evidence-based decisions across marine policy realms. Greater support for marine social science programs and capacity are needed from ocean-focused government agencies, NGOs, and funders. |

A PDF Version of this Policy Brief is available here: Policy Brief – Marine Social Science and Ocean Sustainability

For more information regarding this topic, see the following paper: N Bennett (2019), Marine Social Science for the Peopled Seas, Coastal Management, 47(2), 244-252. (Link)

Contact: Dr. Nathan Bennett (link) is the Chair of the People and the Ocean Specialist Group of the Commission on Ecological, Economic and Social Policy of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (link) and the Principal Investigator of The Peopled Seas Initiative.

New Paper – Navigating a just and inclusive path towards sustainable oceans

I just published a new paper in Marine Policy titled “Navigating a just and inclusive path towards sustainable oceans” (link to paper). This agenda setting paper argues that the ocean science, practitioner, governance and funding communities need to pay greater attention to justice and inclusion across key ocean policy realms including marine conservation, fisheries management, marine spatial planning, the blue economy, climate adaptation and global ocean governance.

Reference: N.J. Bennett, Navigating a just and inclusive path towards sustainable oceans, Marine Policy. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2018.06.001

Abstract: The ocean is the next frontier for many conservation and development activities. Growth in marine protected areas, fisheries management, the blue economy, and marine spatial planning initiatives are occurring both within and beyond national jurisdictions. This mounting activity has coincided with increasing concerns about sustainability and international attention to ocean governance. Yet, despite growing concerns about exclusionary decision-making processes and social injustices, there remains inadequate attention to issues of social justice and inclusion in ocean science, management, governance and funding. In a rapidly changing and progressively busier ocean, we need to learn from past mistakes and identify ways to navigate a just and inclusive path towards sustainability. Proactive attention to inclusive decision-making and social justice is needed across key ocean policy realms including marine conservation, fisheries management, marine spatial planning, the blue economy, climate adaptation and global ocean governance for both ethical and instrumental reasons. This discussion paper aims to stimulate greater engagement with these critical topics. It is a call to action for ocean-focused researchers, policy-makers, managers, practitioners, and funders.

Maintaining coastal and Indigenous community access to marine resources and the ocean in Canada

A group representing academics, Indigenous peoples, fishers, and NGOs recently published a review and policy perspective paper in Marine Policy urging that access for coastal and Indigenous communities should be a priority consideration in all policies and decision-making processes related to fisheries and the ocean in Canada. The ability to use and benefit from marine resources (including fisheries) and areas of the ocean or coast is central to the sustainability of coastal communities. In Canada, however, access to marine resources and spaces is a significant and growing issue for many coastal and Indigenous communities due to an increasingly busy ocean: ocean-related development, competition over fisheries and marine resources, and marine planning and conservation activities that confine activities to certain areas. Loss of access has implications for the well-being, including economic, social, cultural, health, and political considerations, and persistence of coastal and Indigenous communities across the Pacific, Atlantic and Arctic coasts of Canada. The vibrancy and continuity of these communities is important to Canadian society for many reasons, including identity, autonomy, sovereignty, culture, healthy rural-urban dynamics, and environmental sustainability. Greater attention is needed to the various factors that support or undermine the ability of coastal and Indigenous communities to access and benefit from the ocean and how to reverse the current trend to ensure that coastal and Indigenous communities thrive in the future.

A group representing academics, Indigenous peoples, fishers, and NGOs recently published a review and policy perspective paper in Marine Policy urging that access for coastal and Indigenous communities should be a priority consideration in all policies and decision-making processes related to fisheries and the ocean in Canada. The ability to use and benefit from marine resources (including fisheries) and areas of the ocean or coast is central to the sustainability of coastal communities. In Canada, however, access to marine resources and spaces is a significant and growing issue for many coastal and Indigenous communities due to an increasingly busy ocean: ocean-related development, competition over fisheries and marine resources, and marine planning and conservation activities that confine activities to certain areas. Loss of access has implications for the well-being, including economic, social, cultural, health, and political considerations, and persistence of coastal and Indigenous communities across the Pacific, Atlantic and Arctic coasts of Canada. The vibrancy and continuity of these communities is important to Canadian society for many reasons, including identity, autonomy, sovereignty, culture, healthy rural-urban dynamics, and environmental sustainability. Greater attention is needed to the various factors that support or undermine the ability of coastal and Indigenous communities to access and benefit from the ocean and how to reverse the current trend to ensure that coastal and Indigenous communities thrive in the future.

|

KEY MESSAGES Access to marine resources and the ocean is important for the well-being of coastal populations. In Canada, the ability of many coastal and Indigenous communities to access and benefit from the ocean is a growing issue. Access for coastal and Indigenous communities should be a priority consideration in all policies and decision-making processes related to fisheries and the ocean in Canada. Taking action now could reverse the current trend and ensure that coastal and Indigenous communities thrive in the future. |

Recommended actions include:

- Ensuring access is proactively and transparently considered in all fisheries and ocean-related decisions.

- Supporting policy-relevant research on access issues to fill knowledge gaps and enable effective policy and management responses.

- Making data publicly available and accessible and including communities in decision-making processes that grant or restrict access to adjacent marine resources and spaces.

- Ensuring updated laws, policies and planning processes explicitly incorporate access considerations.

- Identifying and taking priority actions now to maintain and increase access, when appropriate and sustainable, for coastal and Indigenous communities.

|

**For more information, refer to the following publication and policy brief: Bennett NJ et al. 2018. Coastal and Indigenous community access to marine resources and the ocean: A policy imperative for Canada. Marine Policy 87:186–193. Link: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308597X17306413 Policy Brief: Maintaining coastal and Indigenous community access to marine resources and the ocean in Canada |

This work was supported by the OceanCanada Partnership through a grant from the Social Science and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) of Canada. For more information, please email myself (nathan.bennett@ubc.ca) or Megan Bailey (megan.bailey@dal.ca).

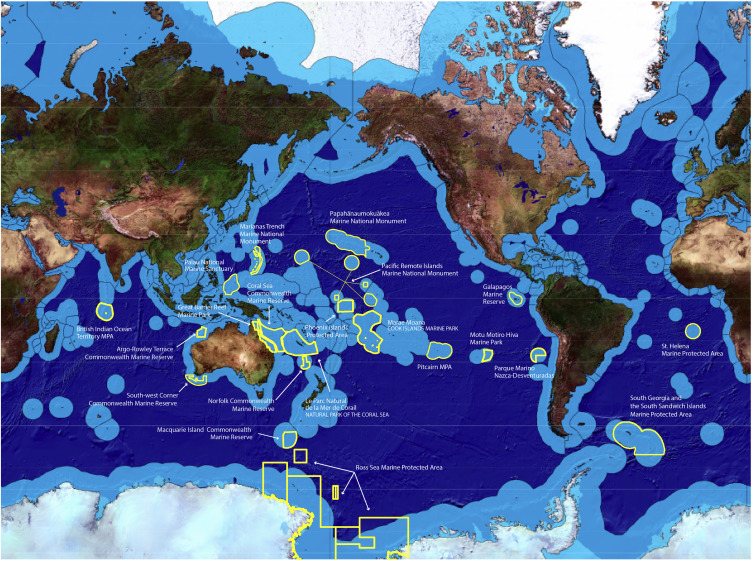

Why people matter in ocean governance: Incorporating human dimensions into large-scale marine protected areas.

Large-scale marine protected areas in 2016-2017 (Source: Big Ocean)

More than two years ago, I took up a Fulbright Visiting Scholar position in the School of Marine and Environmental Affairs at the University of Washington with Dr. Patrick Christie. Along with a team of collaborators from academic institutions and conservation organizations, we began the lengthy process of applying for funding and then co-organizing a global “Think Thank on the Human Dimensions of Large Scale Marine Protected Areas”. The meeting, which took place in February 2016 in Honolulu, Hawaii, was attended by more than 125 scholars, practitioners, traditional leaders, managers, funders and government representatives from around the world. Through facilitating a dialogue with all participants, we aimed to co-produce knowledge at a global scale about how human dimensions considerations might be incorporated into the planning and ongoing management of large scale marine protected areas. The think tank led to a “A Practical Framework for Addressing the Human Dimensions of Large-Scale Marine Protected Areas” and a subsequent academic article (link – see abstract below). This engagement and process demonstrates the benefits of global collaborations and how knowledge co-production processes can lead to the development of both practical and academic insights on global environmental challenges.

Participants of the Think Tank on the Human Dimensions of Large-Scale Marine Protected Areas

Christie, P. Bennett, N. J., Gray, N., Wilhelm, A., Lewis, N., Parks, J., Ban, N., Gruby, R., Gordon, L., Day, J., Taei, S. & Friedlander, A. (2017). Why people matter in ocean governance: Incorporating human dimensions into large-scale marine protected areas. Marine Policy, 84, 273-284. (link)

Abstract: Large-scale marine protected areas (LSMPAs) are rapidly increasing. Due to their sheer size, complex socio-political realities, and distinct local cultural perspectives and economic needs, implementing and managing LSMPAs successfully creates a number of human dimensions challenges. It is timely and important to explore the human dimensions of LSMPAs. This paper draws on the results of a global “Think Tank on the Human Dimensions of Large Scale Marine Protected Areas” involving 125 people from 17 countries, including representatives from government agencies, non-governmental organizations, academia, professionals, industry, cultural/indigenous leaders and LSMPA site managers. The overarching goal of this effort was to be proactive in understanding the issues and developing best management practices and a research agenda that address the human dimensions of LSMPAs. Identified best management practices for the human dimensions of LSMPAs included: integration of culture and traditions, effective public and stakeholder engagement, maintenance of livelihoods and wellbeing, promotion of economic sustainability, conflict management and resolution, transparency and matching institutions, legitimate and appropriate governance, and social justice and empowerment. A shared human dimensions research agenda was developed that included priority topics under the themes of scoping human dimensions, governance, politics, social and economic outcomes, and culture and tradition. The authors discuss future directions in researching and incorporating human dimensions into LSMPAs design and management, reflect on this global effort to co-produce knowledge and re-orient practice on the human dimensions of LSMPAs, and invite others to join a nascent community of practice on the human dimensions of large-scale marine conservation.

New article: An appeal for a code of conduct for marine conservation

A group of colleagues and I have just published an open access paper titled “An appeal for a code of conduct for marine conservation” in Marine Policy. In this paper, we propose that:

- Poor governance and social issues can jeopardize the legitimacy of, support for and long-term effectiveness of marine conservation.

- A comprehensive set of social standards is needed to provide a solid platform for conservation actions.

- This paper reviews key principles and identifies next steps in developing a code of conduct for marine conservation.

- The objectives of a code of conduct are to promote fair, just and accountable marine conservation.

- A code of conduct will enable marine conservation to be both socially acceptable and ecologically effective.

Abstract: Marine conservation actions are promoted to conserve natural values and support human wellbeing. Yet the quality of governance processes and the social consequences of some marine conservation initiatives have been the subject of critique and even human rights complaints. These types of governance and social issues may jeopardize the legitimacy of, support for and long-term effectiveness of marine conservation. Thus, we argue that a clearly articulated and comprehensive set of social standards – a code of conduct – is needed to guide marine conservation. In this paper, we draw on the results of an expert meeting and scoping review to present key principles that might be taken into account in a code of conduct, to propose a draft set of foundational elements for inclusion in a code of conduct, to discuss the benefits and challenges of such a document, and to propose next steps to develop and facilitate the uptake of a broadly applicable code of conduct within the marine conservation community. The objectives of developing such a code of conduct are to promote fair conservation governance and decision-making, socially just conservation actions and outcomes, and accountable conservation practitioners and organizations. The uptake and implementation of a code of conduct would enable marine conservation to be both socially acceptable and ecologically effective, thereby contributing to a truly sustainable ocean.

Press releases and coverage

- Code of conduct needed for ocean conservation, study says – Eureka Alert

- Does marine conservation need a “Hippocratic Oath”? – CBC

- Marine conservation must consider human rights – Nereus Program

Policy Brief: An appeal for a code of conduct for marine conservation (PDF LINK)

Reference: Bennett, N.J., Teh, L., Ota, Y., Christie, P., Ayers, A., Day, J.C., Franks, P., Gill, D., Gruby, R.L., Kittinger, J.N., Koehn, J.Z., Lewis, N., Parks, J., Vierros, M., Whitty, T.S., Wilhelm, A., Wright, K., Aburto, J.A., Finkbeiner, E.M., Gaymer, C.F., Govan, H., Gray, N., Jarvis, R.M., Kaplan-Hallam, M. & Satterfield, T. (2017). An appeal for a code of conduct for marine conservation. Marine Policy, 81, 411–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2017.03.035 [OPEN ACCESS]

Making Real Progress on Marine Protected Areas in Canada

I was in Ottawa last week discussing marine protected areas in Canada. While there, I presented a policy brief titled “Making Real Progress on Marine Protected Areas in Canada” to the All Party Ocean Caucus. The brief can be found here and the text of the policy brief follows below.

Liber Ero Fellows and Members of the All-Party Ocean Caucus, October 24, 2016, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada (From left to right: MP Elizabeth May (Green), David Miller (WWF-Canada), MP Fin Donelly, Dr. Kim Davies (Dalhousie), MP Scott Simms, Dr. Nathan Bennett (UBC/UWash), Dr. Aerin Jacob (UVic), Dr. Sally Otto (UBC).

Making Real Progress on Marine Protected Areas in Canada

Creating effective and successful networks of marine protected areas in Canada requires attention to all elements of Aichi Target 11 and to international best practices for incorporating ecological, socio-economic, cultural and governance considerations.

Federal government ministerial mandate letters 2015, DFO: “Work with the Minister of Environment and Climate Change to increase the proportion of Canada’s marine and coastal areas that are protected – to five percent by 2017, and ten percent by 2020 – supported by new investments in community consultation and science.”

Convention on Biological Diversity, Aichi Target 11: “By 2020, at least 17 per cent of terrestrial and inland water areas and 10 per cent of coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services, are conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well-connected systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, and integrated into the wider landscape and seascape.”

Ecologically significant areas in the Great Bear Sea. Photo credit: Ian McAllister/Pacificwild (pacificwild.org) – Used with permission.

As a signatory to the Convention on Biological Diversity, Canada is striving to achieve the ambitious goal of 10% coverage of coastal and marine areas in networks of marine protected areas (MPAs) by 2020. Key points to ensure that MPA networks are effective and successful are summarized below:

- More than just area – Aichi Target 11 focuses on more than just the amount of area protected (i). Creating ecologically effective MPA networks also requires attention to: representation of all habitats, inclusion of unique and biologically significant areas, connectedness, and consideration of biodiversity and ecosystem service values (ii).

- Management effectiveness – Only 24% of protected areas are managed effectively globally (iii). Effective management requires adequate government funding, capacity and enforcement. Ongoing research programs are also needed to monitor and evaluate social and ecological outcomes and guide adaptive management (iv).

- Integrated ocean and coastal planning – The overall success and effectiveness of MPAs increases when integrated into a broader system of marine and coastal management that takes into account multiple stressors and promotes actions to mitigate the impacts of development (v).

- Socio-economic and cultural considerations – Aichi Target 11 requires that MPAs are “equitably managed” which requires that social, economic and cultural considerations are factored into planning and management. In particular, there is a need to understand and balance the social and economic impacts of MPAs for different stakeholders during network planning and to incorporate cultural considerations and Aboriginal peoples’ rights into management plans (vi).

- Good governance – Good governance during planning, implementation and management is a key to the success of conservationvii. This means that decision-making processes and co-management structures need to be inclusive, participatory and transparent and respectful of the preferential rights of Aboriginal peoples and right relationships with First Nations’ governments (vii).

- “Other effective area-based conservation measures” (OEACBM) – What counts as an OEABCM needs to be clearly defined in the spirit of the Aichi target and in alignment with all the elements listed above (viii). This means that managed areas that benefit only one species or habitat should not be considered equivalent to a marine protected area. Consideration should also be given to other governance models that effectively conserve biodiversity, including Indigenous and Community Conserved Areas and Tribal Parks (ix).

Currently, MPAs cover 1.1% of Canada’s oceans (x)

Getting from 1.1% (497,600km2) to the milestone of 10% is a significant challenge that will require collaboration between multiple levels of government and different jurisdictions. For example, MPAs fall under the authority of Fisheries and Oceans, Parks and Environment & Climate Change Canada. To facilitate the achievement of the targets the government is advised to build on past and ongoing marine planning process of provincial, territorial and Aboriginal governments, such as the Marine Plan Partnership, First Nations Marine Planning, the PNCIMA process and the Northern Shelf Bioregion MPA planning process (xi).

Resolutions:

Fishing boat on the Pacific Coast of Canada. Photo credit: Natalie Ban. Used with permission.

- Ensure that all elements of Aichi Target 11 are taken into account when planning MPA networks in Canada.

- Incorporate lessons from global experiences of creating MPAs related to effective management, good governance and integrated planning

- Account for social, economic and cultural considerations in planning and management of MPAs.

- Develop adequate co-management structures and decision-making processes that include First Nations as equal partners.

- Support multi-jurisdictional collaboration and build on previous initiatives.

- Ensure that MPA planning and management is guided by both natural and social science. Implement monitoring and evaluation to guide adaptive management.

Prepared by Dr. Nathan Bennett (University of British Columbia) and Dr. Natalie Ban (University of Victoria) with input from members of the OceanCanada Partnership (oceancanada.org). Please contact us should you wish further information: nathan.bennett@ubc.ca and nban@uvic.ca

(i) Spalding, M. et al. Building towards the marine conservation end-game: consolidating the role of MPAs in a future ocean. Aquatic Cons 26, 185–199 (2016).

(ii) Jessen, S. et al. Science Based Guidelines for Marine Protected Areas and Marine Protected Area Networks in Canada. 58 (Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, 2011).

(iii) Leverington, F. & et al. Management effectiveness evaluation in protected areas – a global study (2nd ed). (U of Queensland, 2010).

(iv) Pomeroy, R. S., Parks, J. E. & Watson, L. M. How is your MPA doing?: A guidebook of natural and social indicators for evaluating marine protected area management effectiveness. (IUCN, 2004).

(v) Nowlan, L. Brave New Wave: Marine Spatial Planning & Ocean Regulation on Canada’s Pacific. J. of Env Law Prac 29, 151–198 (2016).

(vi) Rodríguez-Rodríguez, D., Rees, S. E., Rodwell, L. D. & Attrill, M. J. IMPASEA: A methodological framework to monitor and assess the socioeconomic effects of marine protected areas. Env Sci Pol 54, 44–51 (2015); Ban, N. C. et al. A social–ecological approach to conservation planning: embedding social considerations. Front Ecol Env 11, 194–202 (2013).

(vii) Bennett, N. J. & Dearden, P. From measuring outcomes to providing inputs: Governance, management, and local development for more effective marine protected areas. Mar Poli 50, 96–110 (2014).; Burt, J.M., et al. 2015. Marine Protected Area Network Design Features that Support Resilient Human-Ocean Systems. Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, Canada.

(viii) Mackinnon, D. et al. 2015. Canada and Aichi Biodiversity Target 11: understanding ‘other effective area-based conservation measures’ in the context of the broader target. Biodiversity and Conservation 24:3559-3581; DFO. Guidance on identifying ‘other effective area-based conservation measures’ in Canadian coastal and marine waters. (DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat, 2016).

(xi) See: http://www.facebook.com/tlaoquiaht/about/; http://www.iccaconsortium.org; Wilson, P., McDermott, L., Johnston, N. & Hamilton, M. An Analysis of Intenational Law, National Legislation, Judgements, and Institutions as they Interrelate with Territories and Areas Conserved by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities – Report No 8. Canada. (Natural Justice, 2012).

(x) Data: http://www.ccea.org; Visualization: www.wwf.ca/conservation/oceans/

(xi) mappocean.org; mpanetwork.ca/bcnorthernshelf/other-initiatives/; mpanetwork.ca

Mainstreaming the social sciences in conservation

I just published a co-authored Open Access article in the journal Conservation Biology titled “Mainstreaming the social sciences in conservation“. In this article, we define conservation social science, examine the barriers to uptake of the social sciences in conservation, and suggest practical steps that might be taken to overcome these barriers.

Bennett, N., Roth, R., Klain, S., Chan, K., Clark, D., Cullman, G., Epstein, G., Nelson, P., Stedman, R., Teel, T., Thomas, R., Wyborn, C., Currans, D., Greenberg, A., Sandlos, J & Verissimo, D. (2016). Mainstreaming the social sciences in conservation. Conservation Biology. Online, Open Access. DOI: 10.1111/cobi.12788

Abstract

Despite broad recognition of the value of social sciences and increasingly vocal calls for better engagement with the human element of conservation, the conservation social sciences remain misunderstood and underutilized in practice. The conservation social sciences can provide unique and important contributions to society’s understanding of the relationships between humans and nature and to improving conservation practice and outcomes. There are 4 barriers – ideological, institutional, knowledge, and capacity – to meaningful integration of the social sciences into conservation. We provide practical guidance on overcoming these barriers to mainstream the social sciences in conservation science, practice, and policy. Broadly, we recommend fostering knowledge on the scope and contributions of the social sciences to conservation, including social scientists from the inception of interdisciplinary research projects, incorporating social science research and insights during all stages of conservation planning and implementation, building social science capacity at all scales in conservation organizations and agencies, and promoting engagement with the social sciences in and through global conservation policy-influencing organizations. Conservation social scientists, too, need to be willing to engage with natural science knowledge and to communicate insights and recommendations clearly. We urge the conservation community to move beyond superficial engagement with the conservation social sciences. A more inclusive and integrative conservation science – one that includes the natural and social sciences – will enable more ecologically effective and socially just conservation. Better collaboration among social scientists, natural scientists, practitioners, and policy makers will facilitate a renewed and more robust conservation. Mainstreaming the conservation social sciences will facilitate the uptake of the full range of insights and contributions from these fields into conservation policy and practice.

Download from here