Tag Archives: Nathan Bennett

Webinar: A Global Spotlight on Ocean Defenders

Video

This webinar titled “A Global Spotlight on Ocean Defenders” aims to bring greater visibility to the plight of Ocean Defenders worldwide. Ocean Defenders include individuals, groups, and communities of small-scale fishers and Indigenous Peoples who are actively protecting the marine environment and human rights. Unfortunately, ocean defenders are often marginalized, criminalized, threatened, and even murdered for their efforts to safeguard the ocean. This webinar explores the ongoing struggles and efforts of ocean defenders globally, and sheds light on the potential avenues through which allies and organizations can provide support and protect ocean defenders.

This webinar will be of interest to a diverse audience of ocean defenders, conservation practitioners, researchers, policy-makers, and funders who are committed to protecting oceans and people. Speakers present an overview of the Ocean Defenders Project, followed by global case studies on Ocean Defenders, discuss potential strategies for effective support, and the ocean defenders themselves will share their lived experiences.

Speakers include:

Nathan Bennett (Global Oceans Lead Scientist, WWF & Chair, People and the Ocean Specialist Group, IUCN)

David Boyd (UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment & University of British Columbia)

Philippe Le Billon (School of Public Policy and Global Affairs, University of British Columbia)

Rocio Lopez de La Lama (School of Public Policy and Global Affairs, University of British Columbia)

Paula Satizabal (Helmholtz Institute for Functional Marine Biodiversity, University of Oldenburg, Germany)

Taryn Pereira (Coastal Justice Network and One Ocean Hub, Rhodes University, South Africa)

Samiya Selim (Center for Sustainable Development, University of Liberal Arts, Bangladesh)

Francisco Araos (Antropologia de la Conservación, Universidad de Los Lagos, Chile)

Kristen Walker Painemilla (Chair, Commission on Environmental, Economic and Social Policy, International Union for the Conservation of Nature)

Recommendations for mainstreaming equity and justice in ocean organizations, policies and practice

Addressing equity and justice issues has become a central concern of ocean policy and sustainability efforts. Yet, many ocean-focused governmental, non-governmental and funding organizations often lack the foundational knowledge, mandate, capacity, and diversity to be able to adequately account for and address equity and justice issues.

In a new opinion editorial, I provide six recommendations for how marine conservation and development organizations can establish a strong internal foundation for mainstreaming equity and justice issues in external marine policies, practices, programs and portfolios. These recommendations include the following:

- Develop awareness of past equity and justice issues in marine policy spheres where the organization works.

- Explore how equity and justice are defined and can be operationalized in marine policy and practice (see Figure 1).

- Mainstream equity and justice in organizational policies, practices, programs, and portfolios.

- Increase organizational human dimensions capacity and ability to think socially.

- Support marine social science research and engage with evidence regarding the human dimensions.

- Commit to internal organizational equity, diversity and inclusion as a foundation for external equity and justice work.

Creating strong organizational foundations is an important starting place and enabler for advancing equity and justice in the ocean. Read the editorial here.

Reference: Bennett, N.J. (2022). Mainstreaming Equity and Justice in the Ocean. Frontiers in Marine Science, 9. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2022.873572/full

Webinar Recording – Equity and Justice in the Ocean

If you missed my recent talk on “Equity and Justice in the Ocean” hosted by the Marine Social Science Network, you can watch a recording here.

The oceans are experiencing a rapid acceleration of both conservation and development activities. When poorly implemented or left unchecked, these activities can lead to environmental and social injustices for the coastal communities and populations who inhabit and rely on the ocean for livelihoods, food security, and cultural survival. In this talk, I examine the types of social injustices that are occurring in the ocean, discuss how social equity can be taken into account in efforts to promote ocean sustainability, and explore priority areas for future marine social science research on equity and justice in the oceans. My aim is to encourage greater engagement with equity and justice considerations in all ocean-focused organizations and in all decision-making processes related to ocean governance and management.

This talk will draw from and build on a number of recent papers related to these topics:

• Bennett, N. J. (2018). Navigating a just and inclusive path towards sustainable oceans. Marine Policy, 97, 139–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2018.06.001

• Bennett, N. J et al. (2019). Just Transformations to Sustainability. Sustainability, 11(14), 3881. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11143881

• Bennett, N. J. et al. (2019). Towards a sustainable and equitable blue economy. Nature Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0404-1

• Bennett, N. J. et al. (2021). Advancing Social Equity in and Through Marine Conservation. Frontiers in Marine Science. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.711538

•Bennett, N. J. et al. (2021). Blue growth and blue justice: Ten risks and solutions for the ocean economy. Marine Policy, 125, 104387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104387

New Paper – Blue Growth and Blue Justice: Ten risks and solutions for the ocean economy

Rapid and unchecked economic development in the ocean can produce substantial risks for people and the environment. But, what harms or social injustices might be produced by the ocean economy? This is the question that we examine in our new paper “Blue growth and blue justice: Ten risks and solutions for the ocean economy” published today in Marine Policy. Through this critical analysis, our aim is to stimulate a rigorous dialogue on how to achieve a more just and inclusive ocean economy.

Abstract: The oceans are increasingly viewed as a new frontier for economic development. Yet, as companies and governments race to capitalize on marine resources, substantial risks can arise for people and the environment. The dominant discourse that frames blue growth as beneficial for the economy, developing nations, and coastal communities risks downplaying the uneven distribution of benefits and potential harms. Civil society organizations and academics alike have been sounding the alarm about the social justice implications of rapid and unchecked ocean development. Here, we review existing literature to highlight ten social injustices that might be produced by blue growth: 1) dispossession, displacement and ocean grabbing; 2) environmental justice concerns from pollution and waste; 3) environmental degradation and reduction of ecosystem services; 4) livelihood impacts for small-scale fishers; 5) lost access to marine resources needed for food security and well-being; 6) inequitable distribution of economic benefits; 7) social and cultural impacts; 8) marginalization of women; 9) human and Indigenous rights abuses; and, 10) exclusion from governance. Through this critical review, we aim to stimulate a rigorous dialogue on future pathways to achieve a more just and inclusive ocean economy. We contend that a commitment to ‘blue justice’ must be central to the blue growth agenda, which requires greater attention to addressing the 10 risks that we have highlighted, and propose practical actions to incorporate recognitional, procedural, and distributional justice into the future ocean economy. However, achieving a truly just ocean economy may require a complete transformation of the blue growth paradigm.

Reference: Bennett, N. J., Blythe, J., White, C. S., & Campero, C. (2021). Blue growth and blue justice: Ten risks and solutions for the ocean economy. Marine Policy, 125, 104387. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308597X20310381

An open access pre-print of the paper is also available at this link: https://fisheries.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2020/06/Take2-2020-02-WP_Blue-Growth-and-Blue-Justice-IOF-Working-Paper.pdf

If you prefer to watch a video: https://youtu.be/Snhl355oJnA

New Paper – Navigating a just and inclusive path towards sustainable oceans

I just published a new paper in Marine Policy titled “Navigating a just and inclusive path towards sustainable oceans” (link to paper). This agenda setting paper argues that the ocean science, practitioner, governance and funding communities need to pay greater attention to justice and inclusion across key ocean policy realms including marine conservation, fisheries management, marine spatial planning, the blue economy, climate adaptation and global ocean governance.

Reference: N.J. Bennett, Navigating a just and inclusive path towards sustainable oceans, Marine Policy. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2018.06.001

Abstract: The ocean is the next frontier for many conservation and development activities. Growth in marine protected areas, fisheries management, the blue economy, and marine spatial planning initiatives are occurring both within and beyond national jurisdictions. This mounting activity has coincided with increasing concerns about sustainability and international attention to ocean governance. Yet, despite growing concerns about exclusionary decision-making processes and social injustices, there remains inadequate attention to issues of social justice and inclusion in ocean science, management, governance and funding. In a rapidly changing and progressively busier ocean, we need to learn from past mistakes and identify ways to navigate a just and inclusive path towards sustainability. Proactive attention to inclusive decision-making and social justice is needed across key ocean policy realms including marine conservation, fisheries management, marine spatial planning, the blue economy, climate adaptation and global ocean governance for both ethical and instrumental reasons. This discussion paper aims to stimulate greater engagement with these critical topics. It is a call to action for ocean-focused researchers, policy-makers, managers, practitioners, and funders.

How the popularity of sea cucumbers is threatening coastal communities

Coastal communities are struggling with the complex social and ecological impacts of a growing global hunger for a seafood delicacy, according to a new study from the University of British Columbia.

“Soaring demand has spurred sea cucumber booms across the globe,” says lead author Mary Kaplan-Hallam, who conducted the research as a master’s student with the Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability (IRES) at UBC.

“For many coastal communities, sea cucumber isn’t something that was harvested in the past. Fisheries emerged rapidly. Money, buyers and fishers from outside the community flooded in. This has also increased pressure on other already overfished resources.”

Sea cucumber can sell for hundreds–sometimes thousands–of dollars a pound. The “gold rush” style impacts of high-value fisheries exacerbate longer-term trends in already vulnerable communities, such as declines in traditional fish stocks, population increases, climate change and illegal fishing.

“These boom-and-bust cycles occur across a range of resource industries,” says co-author Nathan Bennett, a postdoctoral fellow at UBC. “What makes these fisheries so tricky is that they appear rapidly and often deplete local resources just as rapidly, leaving communities with little time to recover.”

Sea cucumber fishing season 2016 (Dzilam de Bravo, Yucatan, Mexico). Credit: Eva Coronado, National Polytechnic Institute, Mexico.

The researchers based their findings on a case study of Río Lagartos, a fishing community on Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula. For the past 50 years, small-scale commercial fishing has been the dominant livelihood of the community.

The town’s first commercial sea cucumber permits were issued in 2013, a significant economic opportunity for fishers in the region. The leathery marine animals are a delicacy in many parts of Asia, and as stocks have depleted there, demand has rapidly depleted fisheries across the globe.

A host of new challenges emerged in Río Lagartos as the sea cucumbers attracted outside fishers, money and patrons, according to the researchers’ interviews with community members.

“Resource management, incomes, fisher health and safety, levels of social conflict and social cohesion in the community are all impacted,” says Kaplan-Hallam. “The potential financial rewards are also causing local fishers to take bigger risks as sea cucumber stocks are depleted and diving must occur further from shore, with dire health consequences.”

Unfortunately, say the authors, this isn’t an isolated situation.

“There are many examples around the world where elite global seafood markets–abalone, sea urchins, sharks–are undermining local sustainability,” says Bennett. “If we want to sustainably manage fisheries with coastal communities, we need a better understanding of how global seafood markets impact communities and how to manage these impacts quickly. Think of it like an epidemic: it requires a rapid response before it gets out of control.”

###

The study “Catching sea cucumber fever in coastal communities” is published in Global Environmental Change

The research was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, MITACS, the Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship program, and the Liber Ero Fellowship program.

New article: An appeal for a code of conduct for marine conservation

A group of colleagues and I have just published an open access paper titled “An appeal for a code of conduct for marine conservation” in Marine Policy. In this paper, we propose that:

- Poor governance and social issues can jeopardize the legitimacy of, support for and long-term effectiveness of marine conservation.

- A comprehensive set of social standards is needed to provide a solid platform for conservation actions.

- This paper reviews key principles and identifies next steps in developing a code of conduct for marine conservation.

- The objectives of a code of conduct are to promote fair, just and accountable marine conservation.

- A code of conduct will enable marine conservation to be both socially acceptable and ecologically effective.

Abstract: Marine conservation actions are promoted to conserve natural values and support human wellbeing. Yet the quality of governance processes and the social consequences of some marine conservation initiatives have been the subject of critique and even human rights complaints. These types of governance and social issues may jeopardize the legitimacy of, support for and long-term effectiveness of marine conservation. Thus, we argue that a clearly articulated and comprehensive set of social standards – a code of conduct – is needed to guide marine conservation. In this paper, we draw on the results of an expert meeting and scoping review to present key principles that might be taken into account in a code of conduct, to propose a draft set of foundational elements for inclusion in a code of conduct, to discuss the benefits and challenges of such a document, and to propose next steps to develop and facilitate the uptake of a broadly applicable code of conduct within the marine conservation community. The objectives of developing such a code of conduct are to promote fair conservation governance and decision-making, socially just conservation actions and outcomes, and accountable conservation practitioners and organizations. The uptake and implementation of a code of conduct would enable marine conservation to be both socially acceptable and ecologically effective, thereby contributing to a truly sustainable ocean.

Press releases and coverage

- Code of conduct needed for ocean conservation, study says – Eureka Alert

- Does marine conservation need a “Hippocratic Oath”? – CBC

- Marine conservation must consider human rights – Nereus Program

Policy Brief: An appeal for a code of conduct for marine conservation (PDF LINK)

Reference: Bennett, N.J., Teh, L., Ota, Y., Christie, P., Ayers, A., Day, J.C., Franks, P., Gill, D., Gruby, R.L., Kittinger, J.N., Koehn, J.Z., Lewis, N., Parks, J., Vierros, M., Whitty, T.S., Wilhelm, A., Wright, K., Aburto, J.A., Finkbeiner, E.M., Gaymer, C.F., Govan, H., Gray, N., Jarvis, R.M., Kaplan-Hallam, M. & Satterfield, T. (2017). An appeal for a code of conduct for marine conservation. Marine Policy, 81, 411–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2017.03.035 [OPEN ACCESS]

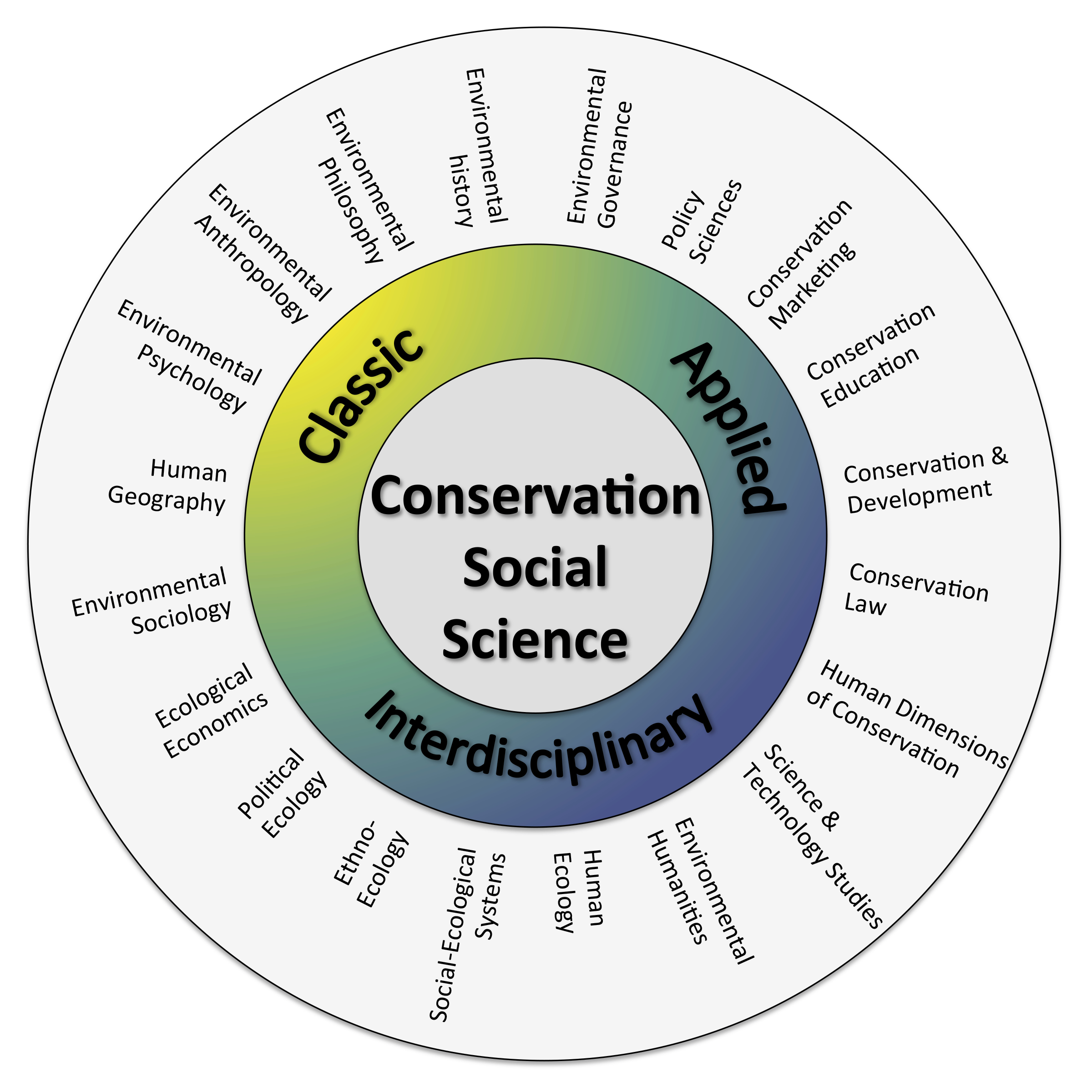

Conservation Social Science: Understanding and Integrating Human Dimensions to Improve Conservation

A group of colleagues and I recently published an Open Access review paper in Biological Conservation titled “Conservation Social Science: Understanding and Integrating Human Dimensions to Improve Conservation“. It can be found here and more information follows below.

Highlights

- A better understanding of the human dimensions of environmental issues can improve conservation.

- Yet there is a lack of awareness of the scope and uncertainty about the purpose of the conservation social sciences.

- We review 18 fields and identify 10 distinct contributions that the social sciences can make to conservation.

- This review paper provides a succinct reference for those wishing to engage with the conservation social sciences.

- Greater engagement with the social sciences will facilitate more legitimate, salient, robust and effective conservation.

Abstract

It has long been claimed that a better understanding of human or social dimensions of environmental issues will improve conservation. The social sciences are one important means through which researchers and practitioners can attain that better understanding. Yet, a lack of awareness of the scope and uncertainty about the purpose of the conservation social sciences impedes the conservation community’s effective engagement with the human dimensions. This paper examines the scope and purpose of eighteen subfields of classic, interdisciplinary and applied conservation social sciences and articulates ten distinct contributions that the social sciences can make to understanding and improving conservation. In brief, the conservation social sciences can be valuable to conservation for descriptive, diagnostic, disruptive, reflexive, generative, innovative, or instrumental reasons. This review and supporting materials provides a succinct yet comprehensive reference for conservation scientists and practitioners. We contend that the social sciences can help facilitate conservation policies, actions and outcomes that are more legitimate, salient, robust and effective.

Reference

- Nathan J. Bennett, Robin Roth, Sarah C. Klain, Kai Chan, Patrick Christie, Douglas A. Clark, Georgina Cullman, Deborah Curran, Trevor J. Durbin, Graham Epstein, Alison Greenberg, Michael P Nelson, John Sandlos, Richard Stedman, Tara L Teel, Rebecca Thomas, Diogo Veríssimo, Carina Wyborn. Conservation social science: Understanding and integrating human dimensions to improve conservation. Biological Conservation, 2016; DOI: 10.1016/j.biocon.2016.10.006

Making Real Progress on Marine Protected Areas in Canada

I was in Ottawa last week discussing marine protected areas in Canada. While there, I presented a policy brief titled “Making Real Progress on Marine Protected Areas in Canada” to the All Party Ocean Caucus. The brief can be found here and the text of the policy brief follows below.

Liber Ero Fellows and Members of the All-Party Ocean Caucus, October 24, 2016, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada (From left to right: MP Elizabeth May (Green), David Miller (WWF-Canada), MP Fin Donelly, Dr. Kim Davies (Dalhousie), MP Scott Simms, Dr. Nathan Bennett (UBC/UWash), Dr. Aerin Jacob (UVic), Dr. Sally Otto (UBC).

Making Real Progress on Marine Protected Areas in Canada

Creating effective and successful networks of marine protected areas in Canada requires attention to all elements of Aichi Target 11 and to international best practices for incorporating ecological, socio-economic, cultural and governance considerations.

Federal government ministerial mandate letters 2015, DFO: “Work with the Minister of Environment and Climate Change to increase the proportion of Canada’s marine and coastal areas that are protected – to five percent by 2017, and ten percent by 2020 – supported by new investments in community consultation and science.”

Convention on Biological Diversity, Aichi Target 11: “By 2020, at least 17 per cent of terrestrial and inland water areas and 10 per cent of coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services, are conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well-connected systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, and integrated into the wider landscape and seascape.”

Ecologically significant areas in the Great Bear Sea. Photo credit: Ian McAllister/Pacificwild (pacificwild.org) – Used with permission.

As a signatory to the Convention on Biological Diversity, Canada is striving to achieve the ambitious goal of 10% coverage of coastal and marine areas in networks of marine protected areas (MPAs) by 2020. Key points to ensure that MPA networks are effective and successful are summarized below:

- More than just area – Aichi Target 11 focuses on more than just the amount of area protected (i). Creating ecologically effective MPA networks also requires attention to: representation of all habitats, inclusion of unique and biologically significant areas, connectedness, and consideration of biodiversity and ecosystem service values (ii).

- Management effectiveness – Only 24% of protected areas are managed effectively globally (iii). Effective management requires adequate government funding, capacity and enforcement. Ongoing research programs are also needed to monitor and evaluate social and ecological outcomes and guide adaptive management (iv).

- Integrated ocean and coastal planning – The overall success and effectiveness of MPAs increases when integrated into a broader system of marine and coastal management that takes into account multiple stressors and promotes actions to mitigate the impacts of development (v).

- Socio-economic and cultural considerations – Aichi Target 11 requires that MPAs are “equitably managed” which requires that social, economic and cultural considerations are factored into planning and management. In particular, there is a need to understand and balance the social and economic impacts of MPAs for different stakeholders during network planning and to incorporate cultural considerations and Aboriginal peoples’ rights into management plans (vi).

- Good governance – Good governance during planning, implementation and management is a key to the success of conservationvii. This means that decision-making processes and co-management structures need to be inclusive, participatory and transparent and respectful of the preferential rights of Aboriginal peoples and right relationships with First Nations’ governments (vii).

- “Other effective area-based conservation measures” (OEACBM) – What counts as an OEABCM needs to be clearly defined in the spirit of the Aichi target and in alignment with all the elements listed above (viii). This means that managed areas that benefit only one species or habitat should not be considered equivalent to a marine protected area. Consideration should also be given to other governance models that effectively conserve biodiversity, including Indigenous and Community Conserved Areas and Tribal Parks (ix).

Currently, MPAs cover 1.1% of Canada’s oceans (x)

Getting from 1.1% (497,600km2) to the milestone of 10% is a significant challenge that will require collaboration between multiple levels of government and different jurisdictions. For example, MPAs fall under the authority of Fisheries and Oceans, Parks and Environment & Climate Change Canada. To facilitate the achievement of the targets the government is advised to build on past and ongoing marine planning process of provincial, territorial and Aboriginal governments, such as the Marine Plan Partnership, First Nations Marine Planning, the PNCIMA process and the Northern Shelf Bioregion MPA planning process (xi).

Resolutions:

Fishing boat on the Pacific Coast of Canada. Photo credit: Natalie Ban. Used with permission.

- Ensure that all elements of Aichi Target 11 are taken into account when planning MPA networks in Canada.

- Incorporate lessons from global experiences of creating MPAs related to effective management, good governance and integrated planning

- Account for social, economic and cultural considerations in planning and management of MPAs.

- Develop adequate co-management structures and decision-making processes that include First Nations as equal partners.

- Support multi-jurisdictional collaboration and build on previous initiatives.

- Ensure that MPA planning and management is guided by both natural and social science. Implement monitoring and evaluation to guide adaptive management.

Prepared by Dr. Nathan Bennett (University of British Columbia) and Dr. Natalie Ban (University of Victoria) with input from members of the OceanCanada Partnership (oceancanada.org). Please contact us should you wish further information: nathan.bennett@ubc.ca and nban@uvic.ca

(i) Spalding, M. et al. Building towards the marine conservation end-game: consolidating the role of MPAs in a future ocean. Aquatic Cons 26, 185–199 (2016).

(ii) Jessen, S. et al. Science Based Guidelines for Marine Protected Areas and Marine Protected Area Networks in Canada. 58 (Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, 2011).

(iii) Leverington, F. & et al. Management effectiveness evaluation in protected areas – a global study (2nd ed). (U of Queensland, 2010).

(iv) Pomeroy, R. S., Parks, J. E. & Watson, L. M. How is your MPA doing?: A guidebook of natural and social indicators for evaluating marine protected area management effectiveness. (IUCN, 2004).

(v) Nowlan, L. Brave New Wave: Marine Spatial Planning & Ocean Regulation on Canada’s Pacific. J. of Env Law Prac 29, 151–198 (2016).

(vi) Rodríguez-Rodríguez, D., Rees, S. E., Rodwell, L. D. & Attrill, M. J. IMPASEA: A methodological framework to monitor and assess the socioeconomic effects of marine protected areas. Env Sci Pol 54, 44–51 (2015); Ban, N. C. et al. A social–ecological approach to conservation planning: embedding social considerations. Front Ecol Env 11, 194–202 (2013).

(vii) Bennett, N. J. & Dearden, P. From measuring outcomes to providing inputs: Governance, management, and local development for more effective marine protected areas. Mar Poli 50, 96–110 (2014).; Burt, J.M., et al. 2015. Marine Protected Area Network Design Features that Support Resilient Human-Ocean Systems. Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, Canada.

(viii) Mackinnon, D. et al. 2015. Canada and Aichi Biodiversity Target 11: understanding ‘other effective area-based conservation measures’ in the context of the broader target. Biodiversity and Conservation 24:3559-3581; DFO. Guidance on identifying ‘other effective area-based conservation measures’ in Canadian coastal and marine waters. (DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat, 2016).

(xi) See: http://www.facebook.com/tlaoquiaht/about/; http://www.iccaconsortium.org; Wilson, P., McDermott, L., Johnston, N. & Hamilton, M. An Analysis of Intenational Law, National Legislation, Judgements, and Institutions as they Interrelate with Territories and Areas Conserved by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities – Report No 8. Canada. (Natural Justice, 2012).

(x) Data: http://www.ccea.org; Visualization: www.wwf.ca/conservation/oceans/

(xi) mappocean.org; mpanetwork.ca/bcnorthernshelf/other-initiatives/; mpanetwork.ca